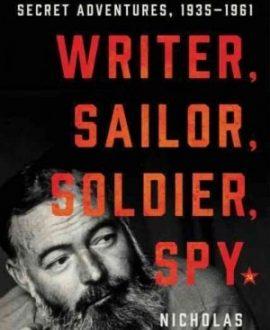

In 1940, as he was preparing to go on a trip to China, the writer agreed to work for the NKVD, the Soviet foreign intelligence agency. Harvey Klehr reviews “Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy” by Nicholas Reynolds.

Before he committed suicide in 1961, Ernest Hemingway raved about being under FBI surveillance and how agents were tapping his phones. Many years later, his friend and biographer A.E. Hotchner charged that his FBI file, released under the Freedom of Information Act, proved that this paranoia was based on reality: that J. Edgar Hoover, worried about Hemingway’s fondness for Fidel Castro and still incensed over his support for the Spanish Republic in the 1930s, had harassed the Nobel Prize winner and contributed to his “anguish and suicide.”

One of the virtues of Nicholas Reynolds’s “Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy: Ernest Hemingway’s Secret Adventures,” is that it shows Mr. Hotchner’s claims were baseless. More important, Mr. Reynolds, a former curator at the CIA Museum, demonstrates that Hemingway was afraid the FBI might uncover a dirty little secret he had hidden for more than 20 years: In 1940 he had agreed to assist the NKVD, the Soviet Union’s foreign intelligence agency. Despite numerous contacts with Soviet agents over a 10-year period, though, Hemingway never did anything of substance for them and, ironically, cooperated far more fruitfully with American intelligence.

Hemingway’s flirtation with the left had begun in 1935. Horrified by the deaths during a Labor Day hurricane of more than 400 World War I veterans, former Bonus Marchers who had been sent to the Florida Keys to work on a federal building project, he wrote an angry article for the Communist magazine New Masses, excoriating the Roosevelt administration for failing to evacuate the men.

Over the following years, as the U.S. Communist Party adopted its Popular Front policy of alliances with liberals and support for the New Deal, he became an ornament in the League of American Writers, a party front, and went to Spain to cover the civil war. Instinctively hostile to fascism and the Spanish nationalist cause, Hemingway celebrated the courage and bravado of the leftist volunteers who flocked to Spain to support the Soviet-backed Republic and even cooperated in the production of a propagandistic film, “The Spanish Earth.” Although he never became a Communist, he denounced those who pointed out their double-dealing, even breaking his long friendship with the novelist John Dos Passos when the latter openly criticized Soviet agents for murdering left-wing opponents in Spain. Hemingway would also fervently defend the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact and urge a friend who had quit the party because of it to return to the fold, because he said only the Russians were fully committed to fighting fascism.

During his long reporting visits to Spain, Hemingway got to know the NKVD general Alexander Orlov, who gave the writer access to guerrilla training camps and allowed him to accompany a sabotage team as he gathered material for what would become “For Whom The Bell Tolls” (1940). American Communists were angered by his negative portrayal of some Comintern operatives in the novel and his admission that the Republic’s forces had also committed atrocities, but Soviet intelligence saw in Hemingway a potential recruit.

In late 1940, as he prepared to go on a reporting trip to China, Hemingway was approached by Jacob Golos, an American agent of the NKVD, and agreed to work for the Soviets, who gave him the code name Argo. Using Soviet files, Mr. Reynolds demonstrates that although Hemingway did secretly see the Chinese Communist deputy leader, Zhou Enlai, during the trip, he never met his Soviet contact. This became a pattern. Despite making a number of promises to help over the next decade, Hemingway never did anything for the NKVD, apparently content to think himself actively engaged in the fight against fascism.

Thirsting for more adventure after Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into World War II, Hemingway persuaded the American ambassador to Cuba to approve his quixotic “Crook Factory,” an ensemble of some 25 bartenders, bums and exiled Spaniards, to do counterintelligence work against supposed German spies in Cuba. Although he produced numerous reports, the FBI was not impressed. Hemingway even outfitted his fishing boat to monitor Axis shipping and search for U-boats off Cuba. He developed a harebrained scheme to enlist Basque jai alai players to fling explosive charges down the subs’ open hatches, somehow persuading government employees to provide him with munitions and radio gear. Luckily, he never encountered an actual German vessel.

Hemingway’s final brush with the world of intelligence came in the summer of 1944 when he hooked up with a band of partisans outside of Paris and, abandoning his role as a war correspondent, organized patrols, gathered intelligence and briefed French forces moving into the capital—activities violating the rules governing reporters in war zones and for which he was investigated.

Far more troubling was his fear that his agreement to assist Soviet ntelligence might become public knowledge. After the HUAC hearings in the late 1940s featured Golos’s ex-lover and exposed the breadth of the NKVD networks in the U.S., Hemingway told Gen. Buck Lanham that he expected to be persecuted by Red hunters because he was a “premature anti-fascist.” While admitting to his wartime comrade that he had done “odd jobs” for the “Russkis,” he insisted that he had done nothing disloyal, but his decision preyed on him.

Yet the onset of the Cold War had done nothing to change Hemingway’s mind about the U.S.S.R. In a letter, he denounced Churchill after his “Iron Curtain” speech as the real threat to world peace, not Stalin, and in another he defended the Soviet purges—the people who “deserved shooting were shot.” He ardently supported Castro and praised the 1959 Cuban Revolution as the fulfillment of his dreams for Spain.

His growing paranoia about the FBI, Mr. Reynolds shows, was fueled by his own reckless decisions. Exacerbated by ill health and years of heavy drinking, it led him to fantasize that he was under surveillance. Hemingway’s suicide was the result of his own demons, not somehow induced by a vengeful government agency. His long-buried secret only confirms that his self-image as an independent anti-fascist was tarnished by his illusions about another totalitarian nation.

Mr. Klehr is the author, with John Earl Haynes, of “Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America.”

Harvey Klehr ©

https://www.wsj.com/articles/hemingway-was-a-spy-1489445646?emailToken=JRryd/p7aX+Wh9AwbMw82VgpaKYXAv7MWVrMaXmPIVDd8SWJ8bP9m/hr24U=

- Hemingway

Kosmospolis Revista digital de Historia, Política y Relaciones Internacionales kosmos-polis

Kosmospolis Revista digital de Historia, Política y Relaciones Internacionales kosmos-polis